Investor Update

How is the company structured. How can you get involved? email the team at --> krishna_at_sequin_dot_bio for additional information

email the team at --> krishna_at_sequin_dot_bio for additional information

1/4/202530 min read

Sequin Bio is structured after Nimbus Therapeutics LLC

Report: Hub and Spoke - Link

So what is Nimbus structure?

Biopharma is a profoundly acquisitive industry. Pharmaceutical giants need to maintain their massive cash flows by developing or acquiring new products—and this balance has swung overwhelmingly towards acquisition over time. This type of “Big Brother” relationship has been around since the biotech industry’s inception, when Genentech first partnered with Eli Lilly in 1978 to manufacture and market recombinant insulin. Genentech was ultimately acquired by Roche in 2009.

This is a blessing and a curse. The massive incumbents provide critical near-term resources but impose a cap on long-term growth—you get snapped up as soon as you have a great product. As Roivant CEO Matt Gline put it, “I think it is interesting the extent to which we lionize [M&A] as sort of the end all, be all. That what success looks like for a biotech company is getting sold.”

So maybe “Big Brother” isn’t quite the right analogy. Attempting to build a generational biotech is a bit like the journey of a baby crab avoiding being devoured by its own mother.

As David Yang traced in a great thread, the critical ingredient for transitioning from a biotech startup to an enduring business is the independent development of a blockbuster drug that brings in over $1B in sales. But this is incredibly expensive to do, so as soon as companies get data hinting at a blockbuster product, there is intense pressure—especially from investors—to sell to pharma, or another biotech looking to make the phase transition to become a “next-gen” biopharma acquirer.1

This is especially tricky for platform companies, which can get bought wholesale for their lead programs before ever getting a chance to compound as a business. Recent examples are the Carmot, Prometheus, and Karuna acquisitions. In each case, the founders decided to launch brand new companies to keep pursuing the original vision of their previous companies.2

What if there was a way to benefit from large M&A transactions while keeping the core platform and team of a company intact over time?

This is exactly the problem that hub-and-spoke biotech companies aim to solve. The innovation is in corporate structure, where a central hub company containing key technology or personnel is fire-walled from spoke companies centered around specific products. With this structure, spoke companies with valuable assets can be sold off to pharma—much like picking a ripe apple off of a branch instead of chopping down an entire tree for one fruit.

To better understand this model—and some of its different permutations—we’re going to cover three important case studies in a new series. We’ll be covering Nimbus Therapeutics, BridgeBio, and Roivant Sciences. Each company has created billions of dollars of value by putting their own spin on the hub-and-spoke structure.

As we compare and contrast these different businesses, we’ll consider many strategic questions. What problem is each business trying to solve with this model? Is the added complexity worth it? Which ideas were viable? Which ideas failed?

For now, let’s get a better sense of how this works with our first case study.

Nimbus Therapeutics

In March of 2011, Bruce Booth, a partner at Boston-based Atlas Venture and industry blogger, published a post with a compelling hook:

Bill Gates has just backed one our new startups – Nimbus Discovery LLC – as part of an extension to the seed tranche. Here’s the press release.

It might come as a surprise to some, but Bill Gates has been a long-time biotech supporter: he was a founding investor in ICOS and was on that Board for 15 years, and importantly, he’s also one of the largest investors in Schrödinger, the world’s leading computation drug discovery company, and our founding partner with Nimbus.

So, with this financing, we’re launching Nimbus out of ‘stealth mode’. Here’s the story.

What? Bill Gates was investing in computational drug discovery back in 2011? It’s like reading a dispatch from the future—but it was written over a decade ago. This was one of the early waves of excitement centered around the idea that computers could revolutionize drug discovery.

This new company aimed to combine three central ideas into a unified whole.

The first big idea, as we can see above, was that advances in computational chemistry had made the technology ready for prime time. These new tools, like Schrödinger’s “WaterMap” software package for modeling the interaction of solvents (in the human body, this is water) with molecular structures, could provide a differentiated wedge for developing new drugs against “exciting but difficult-to-drug” targets.

Schrödinger, which is still a leading company in computational chemistry, was founded in 1990, nearly twenty years before striking this partnership to launch Nimbus. The early 90’s were a very exciting time for computer technology.

The same year Schrödinger was founded, Microsoft made over $1B in revenue—the first time a software company had ever achieved that feat. People were also really excited about the possibility that computers could make drug discovery much more efficient.

Vertex Pharmaceuticals, founded a year before Schrödinger, was based on Joshua Boger’s vision of “rational drug design” with a major focus on computer modeling. Here’s an interesting excerpt from The Billion Dollar Molecule by Barry Werth:

From a business standpoint, what differentiated Vertex’s story—and what Boger now intended to flog most assiduously—were three things: Vertex’s integrated approach, its first-among-equals attention to chemistry, and its lineage, which tracked impressively through the mainline of the pharmaceutical industry and Merck, then Wall Street’s favorite company. “Smart ex-Merck guys making drugs with computers,” Aldrich said, encapsulating.

Vertex wanted to become the next Merck. But Schrödinger wanted something different. Perhaps inspired by Microsoft’s success, the vision for the company was to sell their modeling software to drug discovery companies rather than making drugs themselves.

In 2010, just a year before the Nimbus deal, Bill Gates—one of the biggest believers, and beneficiaries, of the software revolution—invested $10M into Schrödinger. David Shaw, another billionaire very keen on the potential of scientific modeling, was also a key early backer.

I’m reading between the lines here, but the mentality at Schrödinger seemed to be, “We’ve got the resources to invest in hardcore R&D for this software. When it gets good enough, this is going to be an absolutely enormous software business.”

So the Nimbus deal probably seemed like a win-win. Schrödinger could keep focusing on what “made its beer taste better,” as Jeff Bezos would put it, by cranking on software R&D. Setting up a parallel entity that was run by drug discovery experts from Boston would get them closer to the downstream economics of pharma without too much distraction.

This new company would get access to Schrödinger’s scientists, compute, and unreleased algorithms. It would also get target exclusivity—meaning Schrödinger couldn’t turn around and work on the same targets with somebody else. In exchange for all of this, Schrödinger got somewhere around 10% ownership of the company as a founding partner.3

So that’s idea number one: build on top of Schrödinger’s cutting-edge computational chemistry platform.

The second central idea was about how to leverage the computational predictions that were produced. Nimbus was founded in 2009, a year after a global financial crisis. The company wanted to be as capital efficient as possible.4 To do this, their plan was to build a “virtually integrated, globally distributed” model.

First, get model predictions from Schrödinger without needing to build the computational platform. Next, send the first batch of predictions to offshore Contract Research Organizations (CROs) to make experimental progress as cheaply as possible.5 Then, feed the data into the models and make new predictions.

Wash, rinse, repeat.

As Booth put it, “We’re really pushing the envelope on virtual drug discovery.”

The third central idea was to use the hub-and-spoke model.

In theory, they had just established a repeatable process for rapidly producing new differentiated assets at a very low cost. Here, they thought about the problem we outlined earlier. Would they have to start and sell a brand new company for every asset? Yes, but they could do that from within a broader umbrella.

Here’s what they designed:

The Nimbus LLC structure. Source: Abbas Kazimi

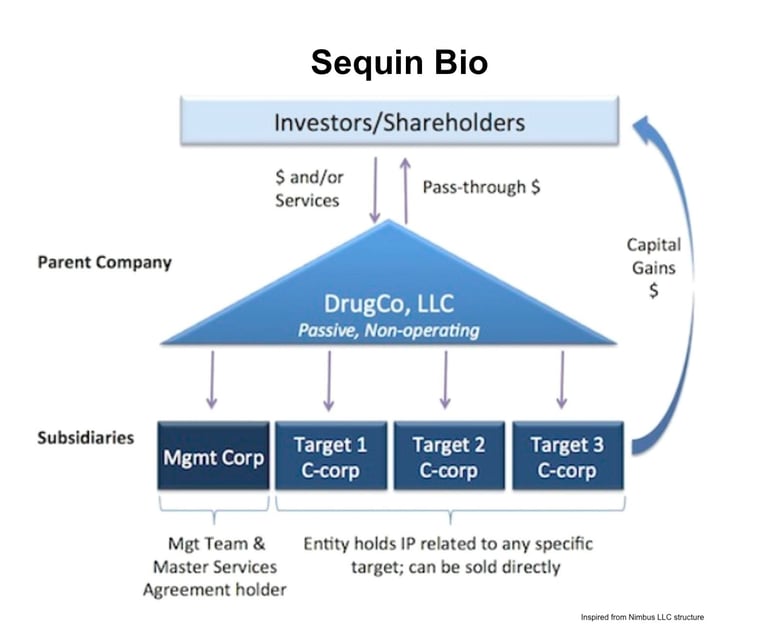

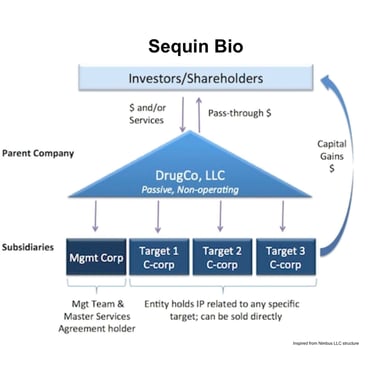

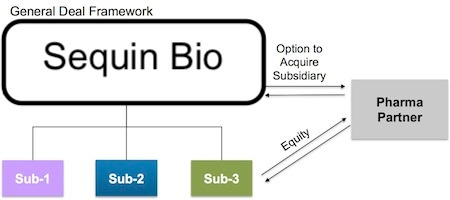

Let’s start at the center. The main hub of Nimbus is a passive limited liability corporation (LLC) holding company. Investors fund this entity. Shareholders like Schrödinger own part of this LLC in exchange for services. This LLC owns a series of distinct subsidiaries—one of which is the actual management company. The remaining subsidiaries house the actual IP related to any specific target.

Any target-specific subsidiary can be sold without impacting the others. These are the apples that can be plucked from the tree.

When apples are plucked (target-specific subsidiaries are sold) the money flows back through the LLC to shareholders and investors. Because the holding company is an LLC, it isn’t taxed like a C-corporation. So the sale is taxed once, not twice. In Booth’s words, this “solves the classic drug discovery illiquidity problem (where it takes 7-10 years to get liquid via M&A or IPO); this LLC structure enables us as shareholders to cycle capital back to our investors in a tax-efficient manner on a per project basis.”

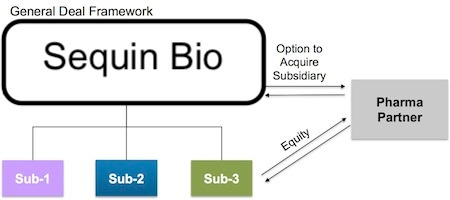

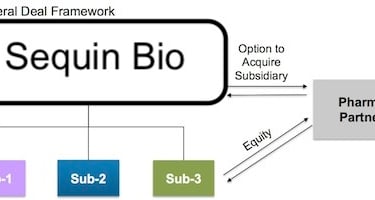

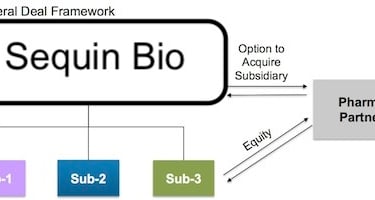

Going a click deeper, here’s a look at the deal framework that this model makes possible:

The Nimbus deal framework. Source: Bruce Booth

Pharma partners (or investors) can make “equity or equity-like” investments in specific R&D programs. These deals provide capital from partners without diluting the parent company, and can even be structured around pre-negotiated terms based on milestones. Nimbus would know upfront how much they would make in a sale if R&D was a success.

It basically creates an “evergreen drug discovery stage biotech” that can continually recycle returns to investors—and to the hub company—and keep cranking on R&D for new projects.

This all sounds really cool in theory. But how does it actually work in practice? Studying this business in 2024, we have the benefit of historical evidence.

Historical Transactions

I won’t bury the lede: this model has worked really well. Nimbus has now sold multiple assets—including a sale worth $4B in cash and $2B in milestones—while keeping the team and platform intact. As the current CEO Jeb Keiper puts it, “The day after a transaction everybody at Nimbus walks back into work and keeps working on the rest of the pipeline.”

This is awesome!

But like any substantial journey, there have been real challenges along the way. The Nimbus team learned which of their initial ideas were viable—and which weren’t.

Early on, the idea was to use the Nimbus engine to crank out a large number of pre-clinical drug programs in parallel. “Invest $10 million to get 5 development candidates in 2 years.” Before even generating data for an Investigational New Drug (IND) application, they’d license these promising assets off to pharma. Simple as that!

But nobody bit. Just like today, the proof is in the clinic—not the computer or the lab. Ultimately, Nimbus needed to file an IND and generate Phase 1 data themselves. But with this data in hand, they were able to make their first major deal.

In 2016, Nimbus delivered it’s “Apollo mission” by selling their Acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) subsidiary (literally named Nimbus Apollo) to Gilead for $400M in upfront cash and $800M more in potential milestone payments.6

This was a big inflection point. They’d now shown that they could rapidly move from one of Schrödinger’s virtual screening hits into the clinic. This sale also proved out the hub-and-spoke model. It truly “enables the sale of the eggs, not the goose.”

But could the goose lay another golden egg?

The Nimbus team got back to work to see. But as their CEO Jeb Keiper wrote, it wasn’t all smooth sailing:

The transition had its challenges though: we had begun working in clinical development, hired staff, and now were reset to an early-stage preclinical company. All our resources in chapter 1 had begun funneling to the lead program, and with only $67 million raised over 7 years, Nimbus was not exactly “robust” at an enterprise-level. We had just 22 people by the end of that year, 15% of the company having departed following the Gilead deal.

Despite the hub-and-spoke structure, the company still needed to concentrate on making sure their Apollo mission could actually reach escape velocity. Once it was gone, they needed to restructure and get back to R&D—which they used 5% of the Gilead proceeds to do.

What happened next highlights the amount of skill, perseverance, and ultimately, luck, that can be behind the big headline deals in the news.

In 2017, Nimbus arranged another spoke deal using the mechanics we discussed above. They gave Celgene options to buy two of their target franchises: TYK2 and STING. According to Keiper, “Nimbus retained full ownership and control of the programs in exchange for funding and pre-programmed exits of $400 million each for Phase 1b data in a few years.”

In theory, this was going to be a rerun of the Gilead deal. But that’s not how things went.

Instead, in 2019, Celgene was acquired by Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS) for $74B. Even in an extraordinarily acquisitive industry, this was big news: it was the largest pharmaceutical acquisition in history.

But for Nimbus, that wasn’t the fact they cared about. It was a much bigger deal that BMS already had a TYK2 program of their own.

This dynamic plunged the company into more troubled water. BMS would want to retain their option to buy Nimbus’s TYK2 program in the event that theirs failed. It was much less certain what would happen if BMS’s program succeeded.

Over the next few years—in the middle of a global pandemic—Nimbus and BMS entered into a legal battle over what would happen with these two programs. The major concern was that BMS would be incentivized to kill Nimbus’s TYK2 program to eliminate competition:

“There is a credible threat that, unless stopped, BMS will slow down or kill the development of Nimbus’s Tyk2 asset. First, BMS has the incentive to protect its leading Tyk2 inhibitor, deucravacitinib, from future competition. Second, BMS has an incentive to avoid additional payments to Nimbus,” the complaint says. “BMS does not have the same incentives to develop Nimbus’s Tyk2, as Celgene did before its acquisition by BMS, given that this would lead to the cannibalization of BMS’s own Tyk2 sales.”

Ultimately, the two companies settled out of court, leaving Nimbus with full ownership of its TYK2 program. At this point, the program had entered Phase 2b trials. With this major twist of fate, Nimbus prepared to finally scrap their hub-and-spoke LLC structure and go public as a clinical-stage biotech.

But that’s not how the story went either! Because of a massive black swan event—the largest pharma acquisition of all time—Nimbus had full ownership of this program. During COVID, Nimbus was also operating in the largest bull run for public biotech stocks of all time. But as their IPO plans crystallized, the market sharply reversed. The IPO window for biotechs swung firmly shut.

The Nimbus management decided to hang tight and continue privately financing this program. This proved to be a wise choice. That year, BMS gained full approval for their TYK2 drug for psoriasis. Most analysts expected that this drug (now marketed as Sotyktu) would come with a severe safety warning because of the risks associated with targeting this family of enzymes. But it didn’t. The allosteric inhibition of TYK2—which was the same mechanism of Nimbus’s drug—now had the potential to grow into a blockbuster autoimmune franchise.

Interest in Nimbus’s TYK2 franchise exploded. Ultimately, Takeda acquired the spoke for $4B in cash and $2B in milestones—ten times the return of the original pre-negotiated Phase 1 deal with BMS.

Today, Nimbus remains a private company. After two major sales, their hub-and-spoke LLC structure remains intact. The engine is still humming. Reflecting on the company’s North Star, Keiper says,

Our mission remains the same: We design breakthrough medicines. Our objective in dollars and cents terms is to again shoot for the moon, to become again a multi-billion-dollar biotech. But our ambition is far greater than that. Nimbus has an opportunity to build a legacy R&D institution. A paradigm of excellence in small molecule drug discovery and development.

With this history in mind, let’s consider the lessons that can be drawn from the journeys of Schrödinger and Nimbus.

Lessons From History

One important nugget from this history is that selling software to pharma is really hard. In February of 2020, Schrödinger went public. Thirty years after their founding, we could see their growth. In their S-1, they wrote, “In 2018, all of the top 20 pharmaceutical companies, measured by revenue, licensed our solutions, accounting for $22.0 million, or 33%, of our 2018 revenue.”

This is a solid business. Schrödinger is currently trading at ~$17 a share, with a $1.29B market cap. Building a billion dollar business is incredible, but it’s a far cry from Microsoft’s growth. The company is also a fraction of the size of Vertex, who pursued a vertically integrated model based on similar ideas. Vertex is now worth over $100B.

Schrödinger appears to have arrived at a similar conclusion. Over time, they’ve evolved to partner on drug development programs—which is where the other two thirds of their revenue comes from. In 2018, they also launched their own pipeline of internal programs. It’s hard to imagine that this wasn’t influenced by their experiences with Nimbus. One of their largest revenue windfalls has been the distributions they received from the TYK2 sale.

As “generative AI” comes of age in biology, many new companies are exploring pure software business models to enable broad access to this technology. History would suggest this strategy captures less value—but purely indexing on history is a foolish exercise in technology. Things change! Studying history helps clarify what would need to be different. If we are ever going to see trillion dollar biotech software companies, the predictions they generate will need to be orders of magnitude better than any existing tools.

And what can we learn from Nimbus’s journey?

The company has proven that the combination of computation and experimental out-sourcing can produce real value. Consider their first ACC transaction with Gilead. Reflecting on the sale, Booth shared some impressive numbers:

Using the ACC program as an example, we achieved a bona fide Development Candidate in roughly 2 years and ~$8M from a novel virtual screen hit at an allosteric pocket. We achieved definitive clinical proof of mechanism in our Phase 1b for an aggregate, fully loaded project spend of ~$20M. These metrics for a first-in-class, chemically novel program are impressive by any measure.

Nimbus also proved that the hub-and-spoke model works. They’ve made two major asset sales while remaining intact as a business, a unicorn feat in the world of biotech platform companies.

I shared some of the gory details of their history because it’s important to understand that their success wasn’t pre-ordained at incorporation because of a clever business model. There wasn’t a smooth pre-meditated path from $400M to $4B between ACC and TYK2. Their trajectory required a lot of hard work, guts, and luck.

And while the model has worked, it didn’t work quite the way they’d originally hoped. When their ideas made contact with reality, they realized that they’d have to prioritize getting their Apollo Mission off the ground. This required ruthless prioritization of their best programs, much like any other biotech.

It’s also interesting to reflect on why the Nimbus team is doing this. Reading through their thinking, it feels like a blend of pragmatism and an intense commitment to an aesthetic ideal.

Pragmatically, it’s extremely challenging—and prohibitively expensive—to build a new commercial organization that supports a blockbuster product.

As Keiper put it, “We knew if we were successful in psoriasis, the implications would require a large multinational company to create the value of global registrations in multiple indications. Given the value of established infrastructure in pharma, it was clear that an M&A acquisition of our TYK2 subsidiary was likely.”

This is part of the deep truth tucked behind the centrality of M&A in the biotech industry. As we saw earlier, most of the generational biotechs were built in the 1980s. At this time, it cost much less to independently develop and commercialize new drugs.

Here’s a crucial excerpt from Matt Herper’s excellent piece on the trial bottleneck:

“Certainly the cost of clinical trials has become so outrageous we have to do something to change it,” said George Yancopoulos, Regeneron’s co-founder and chief scientific officer. He remembers that when he started it cost $10,000 per patient to conduct a clinical trial. Now it can cost $500,000, he said. “Just think how expensive that can be. It really limits what we can do.”

This really needs to change. And it can! As far as I know, the laws of physics haven’t changed since trials cost $10,000 per patient. It’s possible.

But faced with the world as it is, the Nimbus team knew they’d ultimately need to sell the assets they developed. The strong aesthetic ideal expressed in the company is the desire to build an enduring “legacy R&D institution” despite this. They didn’t want to be a one hit wonder—they wanted to build something with staying power.

And the shape of that institution is very specifically designed. In Keiper’s words, “Nimbus is committed to the notion that “small is beautiful” in drug R&D: breakthrough small molecules designed by a small expert team.”

The hub-and-spoke model let them express that vision.

As we’ll see over the course of this series, that’s not the only type of business that can be built with this structure. Over the course of Nimbus’s history, they flirted with going public several times. This would have required changing up their corporate structure and winding down the LLC—which legally can’t conduct a public offering.

This isn’t the only possible outcome. BridgeBio and Roivant Sciences, the next companies in this series, are both public hub-and-spoke biotechs. Although all of these companies have structural similarities, they’ve used this business model to solve very distinct challenges.

Next time, we’ll continue our analysis with another case study.

What other types of enduring businesses are made possible with this structure?

Further Reading

This post wouldn’t have been possible without The Book of Nimbus that Bruce Booth, Jeb Keiper, and many members of the Nimbus team contributed to over the years on LifeSciVC. Most of the source links and quotes derive from these materials. If you want to go deeper on this history, I highly recommend studying this team’s writing.

This type of knowledge sharing is incredibly important for our industry. As I support more biotech companies writing the next chapter of biotech history, I hope to pay it forward by sharing more of what I learn.

Speaking of paying it forward, I hope that we can reduce the cost associated with building businesses like Nimbus over time. This business required a lot of legal and accounting work that many founders don’t want to deal with.

How could we make launching a hub-and-spoke platform as easy as using Stripe Atlas?

Until next time! 🧬

This is increasingly hard to do. As David pointed out, very few biotechs have successfully navigated this transition since the 1980s.

The Carmot co-founders spun out Kimia Therapeutics, the Prometheus founders launched Mirador Therapeutics, and the Karuna founders launched Seaport Therapeutics.

This is the ballpark. Schrödinger owned 3.8% of Nimbus as of 2022, and Nimbus had raised over $400M. I’m assuming a rough ~60% dilution, but it could be higher, meaning Schrödinger’s initial ownership would have been higher.

The initial name for Nimbus was Project Troubled Water, Inc.

The massive expansion of the CRO industry—including offshore CROs in China—made the entire biotech industry much more capital efficient. Ideas can now be tested without building out an entire lab and R&D organization in-house. The BIOSECURE Act now aims to block the use of CROs in countries that are our “foreign adversaries.” If you’re thinking about ways to build low-cost, tech-enabled CROs in the United States, I’d love to talk with you!

They ultimately received $200M in milestones before the ACC inhibitor missed its endpoints. Drugging a different target (TR-beta) led to the first drug approval in MASH earlier this year.

Great blog to follow!

For the brave who want to read everything!!

Source: https://lifescivc.com/2011/03/discovering-nimbus/

And a great VC and blog to follow!

Discovering Nimbus.

Posted March 10th, 2011 inNew business models, Portfolio news

TwitterFacebookLinkedInReddit

Bill Gates has just backed one our new startups – Nimbus Discovery LLC – as part of an extension to the seed tranche. Here’s the press release.

It might come as a surprise to some, but Bill Gates has been a long-time biotech supporter: he was a founding investor in ICOS and was on that Board for 15 years, and importantly, he’s also one of the largest investors in Schrödinger, the world’s leading computation drug discovery company, and our founding partner with Nimbus.

So, with this financing, we’re launching Nimbus out of ‘stealth mode’. Here’s the story.

We founded Nimbus Discovery in 2009 with Schrödinger and have incubated the company here at Atlas for the past couple years. It’s fair to say Nimbus is a rather unconventional biotech, possessing three distinctive features.

Unique Drug Discovery Partnership with Schrödinger provides access to an unparalleled technology suite without the financial burden of having to build it organically. Beyond the sheer breadth of Schrodinger’s software offerings, the crown jewel from our perspective is their new technology for evaluating the energetics of specific water molecules in binding sites called WaterMap™.

Our bodies are 90+% water and yet most structure-based drug design models fail to integrate proper solvent (water) effects with regards to both entropy and enthalpy. WaterMap™ does this. We’ve already found it to be an incredibly powerful tool for identifying specific optimization strategies based on novel water-energy-driven Structure-Activity-Relationships. WaterMap™ is a incredibly well validated technology and has been applied (retrospectively) to about 45 different targets using ligands that have highly heterogenous structures. Not only does WaterMap™ accurately predict binding affinities, it explains SAR that would otherwise be inexplicable. In short, super cool science at the cutting edge of in silico drug discovery.

Our partnership with Schrödinger provides us with far more than just this software package though – we get a large number of dedicated computational chemists, access to thousands of processors via their cloud computing network, new unreleased software algorithms, and exclusivity around specific targets. Continuous, advanced access to the most cutting edge technology applied in a personalized way to our targets allows Nimbus to maintain its first mover advantage.

Moreover, Schrodinger continues to make a huge investment in its platform leveraging an army of ~60+ PhDs and the deep-pocketed support of Bill Gates and David Shaw. (As an aside, it’s probably the only biotech with two billionaires as its top two investors). It is no surprise that Schrodinger has led innovation in the field: the company currently has 50+ peer reviewed publications many of which are among the most heavily cited articles in the in silico modeling space.

Ultra-lean “virtually integrated, globally distributed” R&D operating model to aim for exquisite capital efficiency. We’re really pushing the envelope on virtual drug discovery. We have 10-15x more FTEs working for the company externally as inside the company.

The core team is two incredible individuals (Rosana Kapeller and Jonathan Montagu) who, in addition to being very smart seasoned biotech startup veterans, excel at integrating remote workstreams and collaborators. We’ve got several teams at offshore CRO partners doing biology, chemistry, crystallography, in vivo work, etc…. Not to mention a core set of KOL academic collaborators. We think we’ll be able to work on 3-4 programs with this setup.

It’s paying dividends already: on less than $2M spent, we’ve generated a selective, potent IRAK4 inhibitor (cancer, inflamm) and a set of lead scaffolds against other targets.

One of the key features of the operating model is the virtual integration of all these pieces, with in silico model refinement in the core of the ‘engine room’ so to speak. WaterMap and tools like it depend on constant structural model enhancement, which requires real time integration of project data into our models. Our remote virtual teams interact on almost a daily basis to integrate these new streams of information. This allows us to use these tools for more than just improving selectivity and potency – but also to more precisely know which part of molecules to optimize for PK/ADME concerns as well.

Novel asset-centric corporate structure to promote liquidity and capital velocity. Back in 2009 we spent alot of time figuring out how to leave the limitations of the traditional C-corp structure behind and adopt a more flexible LLC-holding company structure with target-specific subsidiaries as C-corps. A few companies have recently announced they are doing this as well, like Adimab and Ablexis. This structure does a couple very valuable things (beyond creating a job for accountants to track the project financing).

First, it enables project-driven ‘clean’ transactions with Pharma, such that a Pharma can just acquire the target-specific subsidiary and own the IP/assets of a particular program if it so chooses.

Second, and importantly, it solves the classic drug discovery illiquidity problem (where it takes 7-10 years to get liquid via M&A or IPO); this LLC structure enables us as shareholders to cycle capital back to our investors in a tax-efficient manner on a per project basis. Furthermore, it creates this type of ‘deal optionality’ without foregoing any of the traditional benefits of C-corps.

At the end of the day these three elements are great value enablers, but ultimately it’s about the medicines we discover. To pick the targets we sought to generate drugs against, we took an orthogonal approach to traditional “biology” driven target selection. History has shown that generally in silico technologies in drug discovery are helpful tools for the vast majority of targets, but not game-changing. With Nimbus, we wanted to let the technology identify targets where its new insight into SAR was potentially transformational rather than incremental – essentially, to find the rare 10% of targets where these technologies offered a compelling path to new, differentiated chemical matter against hot targets. To accomplish this, we spent the first 12 months of the company screening several hundred ‘hot targets’ in the industry’ pipeline before picking the 10% or so to focus on with Schrödinger.

Our two lead programs today:

IRAK4. One of the most interesting immune-kinase targets in both B-cell cancers (like the IRAK4-dependent MyD88-driven Activated Diffuse B-cell lymphoma [link]) and inflammation. It’s traditionally been very challenging to get selectivity and cellular potency; we’ve managed to generate a series that addresses both of those and aim for a development candidate by end of 2011.

ACC or Acetyl-CoA Carboxylase. A critical enzyme in the metabolism of lipids and a top target for obesity as well as cancer metabolism. It’s been very hard to drug effectively. We’ve managed to get very interesting leads against a unique allosteric domain that should enable a differentiated profile.

Saving the best for last, it’s fair to say our team is exceptional. Rosana Kapeller is our CSO and was founder of Aileron Therapeutics after nearly a decade at Millenium. Jonathan Montagu is our CBO and was with Concert, J&J, Chiron and BCG. The broader team of folks at Schrodinger, like Ramy Farid (President of Schrodinger and founding Board Director of Nimbus), and our chemistry leadership (Ron Wester, Gerry Harriman, Donna Romero, John McCall) are also incredible.

With that rundown, we’re officially out of stealth mode and aiming to close on a Series A soon. Exciting times.

This entry was posted in New business models, Portfolio news. Bookmark the permalink.

Source:

The Nimbus Experiment: Structure-Based Drug Deals

Posted June 27th, 2013 inAtlas Venture, Biotech startup advice, New business models, Pharma industry

TwitterFacebookLinkedInReddit

A couple years ago we unveiled a new startup called Nimbus Discovery LLC which was experimenting with a new model that combined three key elements: Schrodinger’s cutting edge in silico drug screening and design platform, a truly virtual and globally distributed operating model for drug discovery, and an asset-centric LLC-based corporate structure (discussed here).

Although it’s too early to tell what eventual value will be created from this experiment, the company’s early biomarkers are strongly positive. Nimbus has cracked two very tough-to-drug targets of high interest to Pharma (immunokinase IRAK4 and lipid-pathway regulator ACC), and is entering IND-enabling development this year. The technology and virtual operating model have worked well together in efficiently delivering high quality drug candidates.

Importantly, the market validation of the model has also been positive: today Nimbus announced a deal with Monsanto, and last month announced a similar deal with Shire – both involve collaborative drug discovery with a pre-defined path to liquidity around those projects. Given the unique nature of the deals, I thought it would be worth sharing more details and a few general reflections on the model.

Both deals are structured to take advantage of the Nimbus asset-centric approach: they involve equity or equity-like investments in individual R&D programs housed in standalone subsidiaries, alongside an option to acquire those subsidiaries at a specific milestone with pre-negotiated deal economics. These are very enabling for Nimbus: project-based resourcing to support the prosecution of a pipeline with clear value creation points defined at the outset without the need for dilutive funding at the parent LLC level.

These collaborative deals were born out of close relationships Atlas has with both Monsanto and Shire. Over the past few years, both companies have been able to watch Nimbus deliver against its existing programs, in particular for ACC, IRAK4, Tyk2. Here’s the short promotional on their programs’ progress On ACC, it took Nimbus only 16 months from standing start with a virtual screen to get to a fully characterized Development Candidate (DC) with a first-in-class allosteric regulator of the target; for IRAK4, the team has discovered truly selective inhibitors with potent in vivo activity and DC-like profiles; and lastly, they have cracked the Tyk2 selectivity challenge vs closely homologous JAK2 and other JAK family members. The progress of these case studies and the familiarity they had with our team definitely facilitated both transactions. More evidence for why tighter collaborative Pharma/Venture relationships are value-creating.

The bigger picture: why these deal structures make sense

For the biotech, these deals help build a portfolio comprising multiple program-focused entities under an LLC umbrella. In some respects, the pipeline becomes a collection of call optionson individual paths of potential liquidity.

For Pharma, these structures can be tailored to the requirements and sensitivities of each partner, in many cases enabling what could be described as a P&L-sparing, “balance sheet supported” portfolio of innovative projects. This may not always be the interest of a partner, but accessing the otherwise inaccessible cash on the balance sheets of Big Pharma is a definite positive for these deal structures.

For shareholders, including investors and team members, this model secures potential routes to liquidity that accrue as programs are progressed and monetized through development – importantly without having to sell the entire company. In essence this model creates the evergreen drug discovery stage biotech – a real unicorn in the history of biotech (because most drug discovery biotechs have to either sell or become later stage development players to achieve liquidity).

Lastly, the structure has enormous financing flexibility: any individual subsidiary/program can be financed separately if desired – creating options for going longer on specific programs without diluting the parent platform company (or for a new investor, without having to fund drug discovery if that’s not their interest).

Nimbus certainly anticipates doing more of these types of structured transactions, both for its lead programs (IRAK4, ACC, Tyk2) and de novo collaborations around jointly-identified targets. Several of our other platform-based drug discovery companies, like RaNA Therapeutics, are structured in this way and will likely be pursuing deals of this type. Other drug discovery platform biotechs, like Forma and Viamet, have also been experimenting with versions of this LLC-holding company model. Several subsidiary-level deals have been done across the industry (like Forma-Genentech, among others). To my knowledge, none of these have yet to hit their acquisition-triggering milestones. It will be exciting to see what happens when this crop of deals matures to their pre-defined endpoints.

Creatively thinking about new approaches, new business models is part of innovating around the venture model – some experiments will work, some won’t. But the Nimbus experiment feels pretty good right now

SEQUIN DEAL STRUCTURE:

Source: https://lifescivc.com/2014/06/biotechs-virtual-reality/

Biotech’s Virtual Reality

Posted June 4th, 2014 by Jonathan Montagu, in From The Trenches, New business models, R&D Productivity, Translational research

Much has been written about the merits and demerits of the virtual biotech model. In essence, a virtual biotech outsources all non-core activities and rejects the need for in-house laboratories. Instead, a small internal team manages execution outside the company, generally through contract research organizations (CROs). Such companies have led to successful exits and IPOs – Ferrokin, Artaeus, Stromedix, NovaCardia, Stemline – but have principally focused around specific, clinical-stage assets.

To our knowledge, Nimbus Discovery is the first company to have established a drug discovery platform entirely through a virtual, distributed model. Nimbus conducts drug design and computational chemistry itself but has no in-house laboratories. Over the past four years, we have established a complete small-molecule discovery and development platform that spans early discovery through to early development. We have six on-going programs across three therapeutic areas, all managed by a lean team of twelve internal employees that directs approximately eighty external FTEs across three continents.

The rise of the virtual company

Virtual drug discovery was initially a response to the high cost of capital for startups and the significant burden of fixed infrastructure, but true enablement of the approach has only been possible comparatively recently: a rich CRO ecosystem is now in place giving small companies access to every conceivable R&D capability; massive Pharma layoffs have enhanced the accessible talent pool; CROs in lower-cost geographies such as China and India offer higher quality services with an improved user interface; and communication tools, such as inexpensive videoconferencing, have made cross-border collaboration much more feasible.

Moreover, the successful adoption of the distributed model in other industries provides a blueprint for the life sciences. In the semiconductor industry, ARM Technologies designs microchip layouts that use markedly fewer transistors than traditional approaches offering speed, efficiency and cost advantages. Unlike its fully-integrated competitors, ARM does not manufacture its own chips. Instead, it licences its designs to hundreds of chip manufactures worldwide, receiving high-margin royalties in exchange. ARM-designed chips are now present in 95% of smart phones, highlighting how pervasive a company without a manufacturing base can become.

Successes and surprises

Nimbus Discovery was designed to push the virtual approach to the limit – a “radically virtual operating model”, as we called it – based on the assumption that it would be better, cheaper and faster than bricks-and-mortar approaches. At the time, naysayers argued that the approach would be disadvantaged from a speed and data quality perspective due to perceived loss of control and coordination.

But has the model worked out as everyone expected? Well, there have been some successes and some surprises.

Nimbus has focused on largely intractable targets where the rest of the industry has struggled to achieve clinically-viable drug candidates due to poor potency or selectivity, off-target safety risks, or inadequate drug-like-ness. Despite this, Nimbus has brought two programs to Development Candidate (DC) stage for targets where many others have broken their pick axes. This, I believe, provides substantial validation for the Nimbus model and our underlying technology.

In benchmarking against other portfolio companies, I feel that we hit the ball out of the park for our program targeting the lipid master regulator, Acetyl CoA Carboxylase (ACC), where we were able to go from virtual screen to DC in 16 months. Our IRAK4 program delivered a Lead Candidate four months after virtual screen but we then spent substantially longer improving pharmaceutical properties.

Our model appears to be far cheaper and faster early in discovery, where generating superb drug-like hits and leads is the goal, but in the latter stages of drug discovery, such as final lead optimization and candidate selection, the costs and time we have faced look a lot like other quality biotech campaigns around ADME, toxicology, PK, etc. If you have a starting point without downstream liabilities in those areas, often proven empirically, it translates into some startlingly good metrics. This teaches us how we can further improve our time/cost to DC metrics: by ensuring that we have multiple, structurally distinct scaffolds to take into Lead Optimization, we can choose the best to expedite our path to DC.

As previously noted, we have a different cost structure to traditional biotech. Only 10-15% of our cost is fixed and most of the variable cost is spent with external CRO’s that can titrated up and down at very short notice. This allows us to allocate resource dynamically based on program requirements on a month-to-month basis. This is in contrast to high fixed-cost models where decision-making is driven by how to deploy, and pay for, the annual costs of buildings, labs and an installed employee base. Feeding the infrastructure becomes an important part of those models. Since the vast majority of our resources at Nimbus are fungible, we can make business decisions that are truly data driven.

Looking under the hood

So how has this been achieved and where do we still have hurdles to overcome in operating this model? I believe that the key success drivers for the Nimbus model are people, programs and partners.

People

The Nimbus drug discovery platform consists of a distributed ‘network’ of team members that can efficiently share ideas, information, data and compounds. This has allowed us to cherry pick the best talent across the globe rather than relying solely upon the talent pool in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Similarly, we have recruited the world experts around certain target biologies to run key aspects of programs, in a way that they feel truly part of the team. As a Brit, it gives me great warmth to say, “the sun never sets” on the Nimbus team.

Program leaders at Nimbus are then tasked with marshaling resources outside the company to generate the required datasets and meet aggressive timelines. This requires well-seasoned R&D executives that can design, and then manage, science at a distance. Scientists that thrive within the Nimbus model are strong individual contributors that have a collaborative spirit and can motivate through influence rather than direct reporting relationships.

By outsourcing non-core activities, we reduce the footprint of the organization allowing our scientists to focus on doing science rather than addressing HR issues and writing performance reviews. There’s also no room in the Nimbus model to build an empire … but this is precisely the point. Empires lead to silos and politics, both of which compromise good decision-making.

This type of approach is not for everyone. Most scientists have been trained to trouble shoot experiments that they can touch and feel. The distributed model places the control of execution in the hands of others, often many time zones away and it takes a significant time commitment to manage these external relationships. Also, many senior executives are used to the infrastructure associated with larger companies, none of which is present at Nimbus. The Nimbus model demands that the entire team roll up their sleeves and regularly ‘helicopter’ from high-level strategy to the details of experimental design.

Since we work so differently at Nimbus, finding the right people has been challenging and, given the small size of the organization, every hire must be vetted extremely carefully. That said, we have been able to attract a cadre of seasoned R&D veterans that think differently, an important differentiator given Nimbus’ focus on previously intractable targets.

Programs

Despite the success of the Nimbus model, I do not believe that it is appropriate in all cases. Nimbus principally works with well-understood but historically challenging targets, known modalities and established chemistries. Assays, experiments, and chemistry can all be accessed creatively in the external marketplace but I would not try to implement a novel RNAi, peptide or biologics platform using the Nimbus model. For these approaches, the core value proposition is based on proving out a new therapeutic modality to create entirely novel biological underpinnings. Such skills are, by definition, not available within CROs.

In situations where we have had to explore new biology, e.g. IRAK4’s role in tumorigenesis, we have adopted a more standard model that involves some rented lab space and some talented biologists. At times, we have also enlisted the help of US-based chemists to solve hard synthetic chemistry problems as we scaled synthesis for IND-enabling studies.

Partners

The commitment of strong technology partners is key to the success of the Nimbus model. Schrodinger, a key technology and co-founding partner, has been instrumental in the success of Nimbus and are core team members in the “engine room” of the company. Beyond computational insight, we’ve embraced dozens of other partners. This has involved careful screening of potential collaborators but also a healthy amount of empiricism.

Frankly, we still find it challenging to find true full-service CROs, and our bias continues to be towards cherry picking capabilities from the best global CROs but this obviously comes with a complexity burden. To address these issues, we have looked for creative ways to align incentives and share risk. To make sure that we get the A team working on our projects, we have implemented success-based milestone arrangements; preferred-partnership agreements that ensure enhanced access to services and turn around based on volume of work; and bonus awards to individual scientists.

Despite tremendous growth in the ecosystem, there are still areas where the CRO footprint is more limited. On the biology side, Asian CROs are adept at primary assays and off-the-shelf ADME readouts but often struggle with bespoke biology. This is compounded by import restrictions into China for assay kits and lack of infrastructure for donor tissues, both of which are commonplace in the US. This situation will undoubtedly change over time and we are aware of certain Asian CROs that are now establishing US-based teams to develop custom assays which can then be transferred to China once protocols are robustly established.

For complex biology, we have also made extensive use of academic collaborations. This should be a blog post in its own right but we have found that these relationships can generate pivotal datasets and, if successful, can build excitement amongst the medical community.

Beyond capital efficiency

The Nimbus operating model was initially conceived as a route to improving capital efficiency and productivity for tackling hard-to-drug targets, which it has clearly delivered on … but the reality of the model, I believe, goes well beyond that and is much more exciting. We have established a new way of doing drug discovery that redefines how we innovate. The Nimbus approach is inherently more nimble and flexible, and unencumbers scientists to think about science rather than organizational issues. Nimbus is as much about the mindset of its team as it is about the underlying technology. This mindset is expressed through the configuration of our organization: function follows form in the same way that flexible thinking maps to fungible resources.

For the right type of projects, I believe that the “Nimbus experiment” in virtual R&D represents an important drug discovery model for the future.

Innovation

Pioneering advancements in biotechnology for developing new drugs. Providing low cost custom formulations, generic and off patent drugs for repurposing in rare and orphan diseases.

Research

Sign Up for updates

Generic finished formulations

Oncology drugs in development

© 2024. All rights reserved.